Jarrah

James, Bella Rogers, Caitlin Graham and Kaitlyn Patterson

The flourishing urban civilisation prior to the Black Death

in 1348 was based upon the growing economic prosperity that can be found in

Italy, in particular Florence and Venice which would come to be capitals of the

Renaissance to come. However powerful

and influential these two cities were, both relied and built their economies on

different foundations. Florence built repute through the establishment of an

effective banking system that allowed for growth through the merchants and

guilds. The close relationship between the leaders of Florence and the papacy

meant greater military and political support and also allowed for the newly

improved banking system to ‘act as the pope’s fiscal (tax) agent. This action

allowed some merchant companies to grow and transform into the banking

profession.

The second economic growth industry in Florence at this time

was in wool. Wool in Florence within this period is described as the most

luxurious and expensive of commodities. The trade prices on wool allowed for

the industry to expand, encompassing a larger amount of the population and

lowering unemployment rates, due the arduous production processes.

Unlike Florence, Venice did not find its economic niche in

wool. The Venetian industry was built on trade, which during this period relied

heavily upon the construction of ships and administration of fleets. Through this industry Venice was able to gain

independence from the Byzantine Empire by 1000.

The flourishing urban civilisation of the proto-Renaissance

era can also be seen through the expansion of population in and around Florence

and Venice, through the construction of public spaces and buildings such as

churches, guildhalls, government buildings, palaces, hospitals, walls, and

roads. These constructions were erected to match the growing prosperity among

the merchant classes. In particular, walls highlighted the growing city

population as walls were built to replace the pre-existing roman boundaries

which had served as security up until this time.

|

| Florence wall construction c.600-1284 |

Francis or Francesco Petrarch (1304-1374) is a

perfect example of the blossoming of the Renaissance thought in the ‘cultural

explosion’ prior to the Black Death. He

was a noted scholar, as well as poet whose extensive body of work was

significant in the development of European literature. What makes Petrarch the

ideal Renaissance man is his study of classical antiquity; he reflects on the

past to promote social reform for the future.

|

| Petrarch |

In the extract letter to Posterity, Petrarch displays a then

unique exploration of human thought and mind, in particular an exploration of

himself, which was a new approach in the literary world. Petrarch’s letter

adopts a humble and self-conscious tone; he is both expressing hopefulness that

his legacy will live on through his work, and also modesty, as he recognises

that as one man, he is insignificant in the greater scheme of things. This

critical self-analysis is only one of his many works, however it shows a new

development in expression of thought. It

furthermore provided the intellectuals of later generations with inspiration, for

the examination of oneself in order to produce moral judgement became popular

amongst scholars.

Venice was originally under Byzantine rule until it gained independence when the Byzantines lost control of the area in the 9th

century. Venice’s economy was primarily based on mercantile trade, and

the building of ships, to the extent that the state funded the construction of trade convoys, and the most powerful merchants were those involved in the running of the state. In 1279 the Grand Council, made up of the city’s wealthy founding families, voted to close membership, turning the merchant elite into heredity noblemen. While any Venetian was free to make money to the degree that his or her skill allowed, excepting a few select instances, all were barred from taking part in the instrument of government unless born to it. And yet, there was little objection or resistance to this, unlike in Florence...

Florence was run by nine priori, each elected for two-month terms. Six were from the major guilds, and the remaining three were chosen from among the minor guilds. These guilds each dedicated to a given trade,

counted a large portion of the working Florentine population among their members – but not all of them. The Ciompi, labourers and wool-workers of varying skill employed by the wool merchants’ guild, but not actually members, could take no part in civic decision-making. They rose up in rebellion in 1378, compelling the Oligarchs to give them guild and citizen rights. The ciompi priori attempted to affect political change from office, but a few months later the traditional guilds took up arms, and dissolved the new ciompi guilds.

Jurists, or specialists in Roman law, the basis for many law codes throughout Italy, came to prominence in the 11th and 12th centuries, as they helped found the laws of the developing communes. Some individuals, Marsilius of Padua and Bartolus of Sassoferato, also contributed significantly concepts of political theory in the 12th and 13th centuries.

|

| 14th century Venice |

The Black

Death had an enormous impact on medieval society, primarily because of a huge

loss of population. Although the number of deaths due to the Black Death is

disputed, King estimates is as between one and two thirds of the population

throughout Western Europe. This significant loss of life had a profound impact

on the economy, as a huge number of labourers had been killed, leaving

positions vacant. This saw an increased demand for workers, and a consequential

rise in the average wage of the peasants. It also significantly impacted on the

feudal system, as lords found themselves without tenants to cultivate their

land, and the costs of rent dropped dramatically as a result. As you can imagine,

without the workers to tend the land, there was a marked drop in the production

of agricultural goods, and the revenue accrued.

The nature

of the plague meant society was literally helpless to resist it. Medicine was

not of the standard required to combat the plague, and the methods of

prevention were often far-fetched and fanciful. Loss of population meant many

homes and even cities were abandoned, with the occupants having either fled or

perished. Furthermore, because of such exposure to death, society became rather

blasé the sight of it. In a first had account written by Agnolo Di Tura, he wrote that: “There were none that wept for any

death, for everyone expected to die. And so many died, that everyone thought it

to be the end of the world.”

|

| Monks with plague, late 14th century illuminated

manuscript |

Whilst the Black Death has significant social and economic impact, it

was not the sole causative factor in the end of the medieval era and the

beginning of the renaissance era. As evidenced by Florence and Venice, the

social reform of the renaissance was already occurring in a pre-plague Europe.

The historian Joseph Byrne sums this concept up nicely when he states; “the

Black Death…was much more of a catalyst of change in the West than an

instigator of it.”

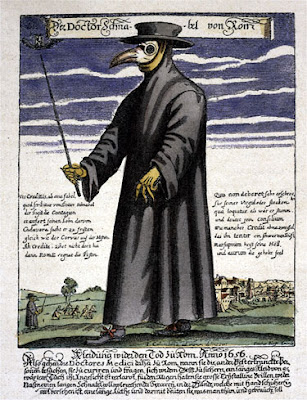

A plague

doctor. The mask was based on a popular theory of the time that the plague was

carried by infected, bad air. This mask apparently filtered the air, thus

enabled proximity to the infected.

Blog

question: in your opinion, did the Black Death merely enhance the significant

change already occurring in the late medieval era, or did it have its own

independent social and economic consequences?